Nanny passed away last month on May 22. Her name was Ann (I got my middle name from her) but everyone called her Nan.

You can read her obituary here; but this is my tribute to her.

On the plane ride home from her funeral, I watched The Room Next Door: a movie that’s all about death and dying. It starts with the following exchange:

“You said you wrote this book to better understand and accept death.”

“Yeah, it feels unnatural to me. I can’t accept that something alive has to die.”

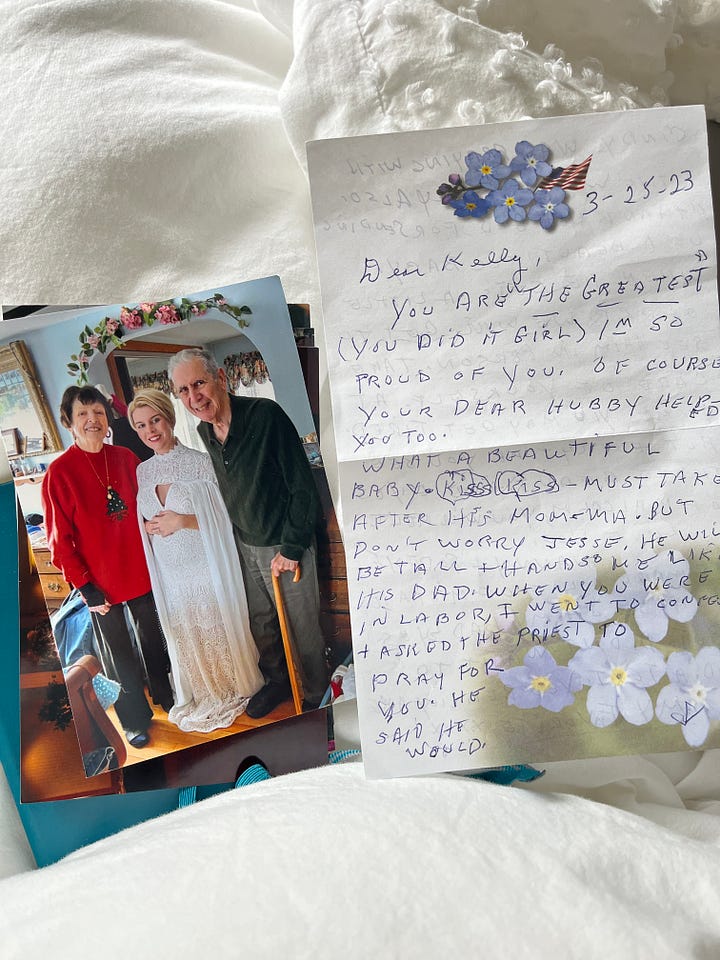

Weeks later, I still feel that way. Every time I look at a photo of Nan or read the letter she wrote me after Mal was born, I can hear her voice in my head: “Dear Kelly, you are the greatest. You did it girl. I’m so proud of you.”

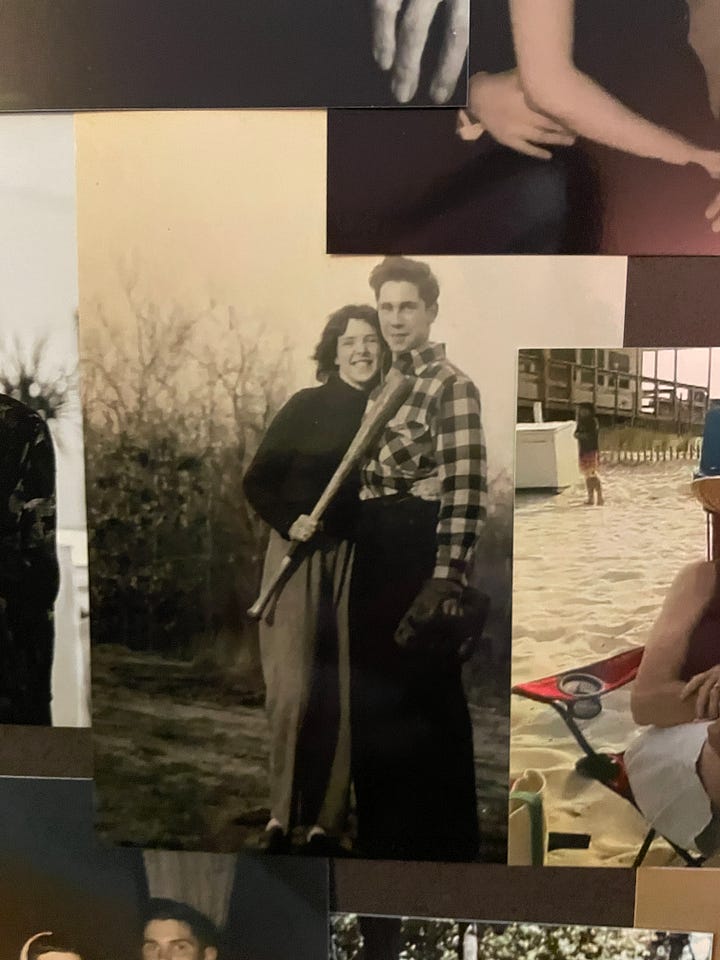

Nanny was our matriarch—the only word that’s powerful enough to capture her impact on our sprawling extended family. She was a wife, a mom to six kids, and a grandmother to 25 of us, and she fulfilled those roles with the spirit of a grand marshal in a parade.

But she was also a writer, a storyteller, an entertainer, a ringleader, a fierce believer, a night owl, an antique seller, a fortune teller, a counselor, a peace maker, and a proverb dispenser.

Oh my god, the endless well of proverbs.

Nan would jokingly refer to company as “comp-agony.” She would warn you to never put shoes on a table or else you were doomed to either kiss a fool or get in a fight. When I was pregnant, she came to my baby shower and gave me a battle cry to take with me: “I’m a strong woman. I can do it.”

But my favorite saying of hers was, “What is for you won’t go by you.” Anytime I was worried about the outcome of something or disappointed that I didn’t get what I wanted, she would remind me of that in an incredibly convincing, “and that’s settled” kind of tone. Plenty of things that I wanted in life have sailed right by me, and it’s always comforting to think that they simply weren’t right for me.

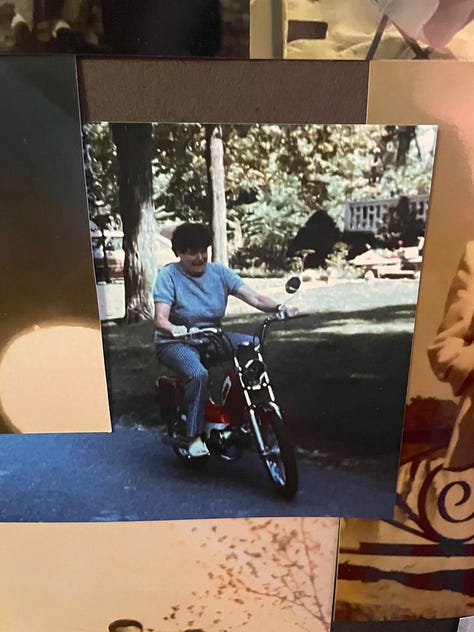

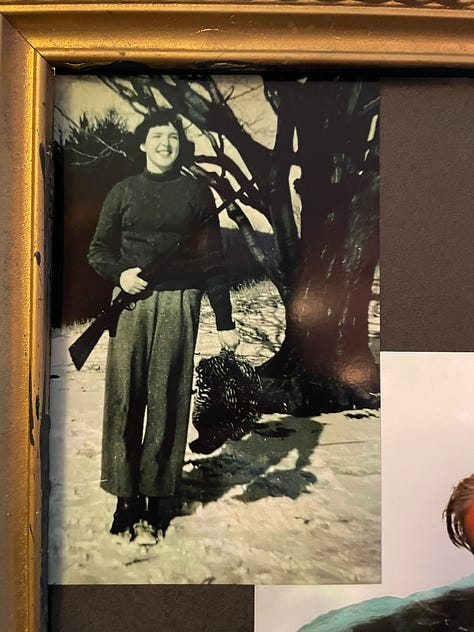

Nanny was tall—between her height and her energy, she was never afraid to take up space in a room. She had a gap in between her two front teeth that added a kind of mischievous charm to her big smile. She loved to dress up. She often wore bold shades of red and sometimes sequins, or even a hot pink wig if the occasion called for it. (We would dress up with her too: one time she let me and my sisters raid her closet and we all dressed up as hippies together. We called it a hippies party. We were never bored at Nanny’s house.)

One of her most iconic costumes was that of Madame Natasha.

Madame Natasha was Nan’s long-lost twin sister who would appear sporadically out of nowhere, dressed like the nomadic fortune teller that she was: all flowing scarves and jangling jewelry and thick black hair flowing freely down her waist. We’d always get excited when Madame Natasha appeared on the scene because it meant that someone was about to get their tea leaves read.

Unfortunately, she may have been a little too good at her craft because some people took it more seriously than it was meant to be. One day Nan’s friend told her that she had decided to divorce her husband after having been inspired by the results of her tea leaves. After that, Madame Natasha retired and never visited us again.

Stories—her own and other people’s—were a huge part of Nan’s life.

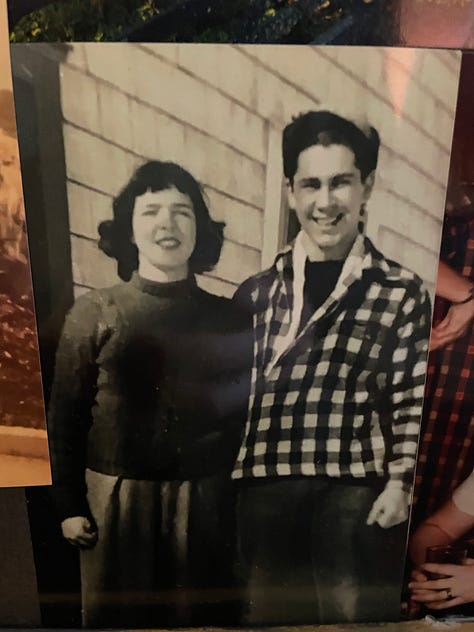

She always said that her favorite job was when she worked as a ticket agent in a bus station because she got to hear strangers’ stories. She also loved to tell us the stories of her life, like how she met Popeye when she was sitting on her brownstone stoop in Manhattan and he demanded a kiss (that she of course refused). A mainstay of my childhood was the “Little Timothy” stories that she made up for our bedtime entertainment.

She also wrote purely for herself. Nanny was the only person I knew growing up who was a writer. I remember her showing me what she was working on for her writing class and asking for my opinion, as if my teenage self was an expert on writing. Most of them were essays about her life.

Here’s a short essay she wrote that started with the definition of “authority”:

“If you have ever watched old movies, you know that in a Western the sheriff, a good guy, always wears a white hat and the bad guy a black hat.

In my family I always had to wear the black hat. Whenever my children would ask their father to do something or go somewhere, he would say: “Ask your mother.” His white hat never got soiled. When they would come to me, I would ask all sorts of questions: “Where are you going? Who are you going with? Are their parents home?” Shaking my head I would determine that I didn’t think it was a good idea. With my children wailing and mashing of teeth, I would put on my black, tattered hat and hide in the kitchen. I knew this would be a safe place as no one ever wants to be caught working in there.

While washing the pots my favorite daydream would be me, wearing a big, white sombrero and telling my little darlings, “Of course you may do anything you want to do, but you better ask your father, he has his big black hat on.”

I want to gather up all of her writing in one place so we can pass it down as a family heirloom.

I also want to share so many more memories I have of her: how she made our childhoods so magical in that big yellow Victorian on top of the hill, how she taught me to blow my nose properly and let me sleep over and made me banana splits, how she only ever got mad at me one time (when I gave her a fright by disappearing to drink a Mike’s Hard Lemonade in the woods) and then forgave me and never spoke of it again, how she praised my earliest attempts at writing over and over again and made me believe I was good enough to be a writer.

There’s so much more I could say about her. But I think I’d rather end with more of Nan’s words.

The day before her funeral, I read this excerpt from an essay she wrote about the death of her friend Helen:

“... the next wave rolled in and covered the footprints. I looked for them but they were gone. I remember thinking, just like life. We’re here for such a short time. We make our mark and then we’re gone. Life is very fragile and precious. Will someone remember me? Did I do something important? Will I have left this world a little better than it is now?

My thoughts went back to Helen. She would have been very annoyed at me, wallowing in sadness. I pictured her telling me to stop this nonsense. She’d remind me that I made her laugh and ask me if I didn’t think that making people laugh was leaving my mark in this world. I guess I would have to agree, remembering all the fun things we did and all the laughs we had. If I could see her one more time, I would smile and say, ‘Helen, you certainly left your mark on me. Thank you dear friend, you left your footprints on my heart.’”

Nan, so many people will remember you. I worry that you didn’t even realize the mark that you made on this world. Not only did you make people laugh but you entertained us, advised us, loved us, and inspired us. You gave me a road map of how to live. So much of who I am today is just stuff that I took directly from you.

Every time I have a Deevy breakfast, make a banana split, pray to Saint Anthony to help me find what I’ve lost, tell someone’s fortune with my tarot cards, recite one of your sayings, wear red for a boost of confidence, or write a story, I’ll be keeping a piece of Nanny alive in the world.

I will pass these pieces of Nanny down to Malcolm—and his sibling if he ever has one. And if they ever have children and I’m lucky enough to step into the role of Nanny, I’ll pass it all down to them as well.

Nan: I think I speak for everyone who knew and loved you when I say, thank you for the laughs.

Love always, Kelly

I love this so much!!! Very well-written! She was such a beautiful breath of fresh air. I absolutely love the part about “What is for you won’t go by you.”

So many good Nanny quotes! I can picture her laugh in my head right now and it’s so soothing. I miss her so much 💔💔

What is for you won’t go by you is one of my absolute favorites too- so beautifully said, Kelly! ❤️